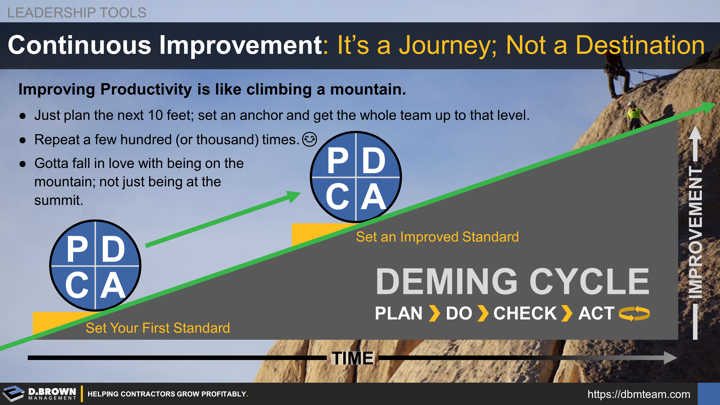

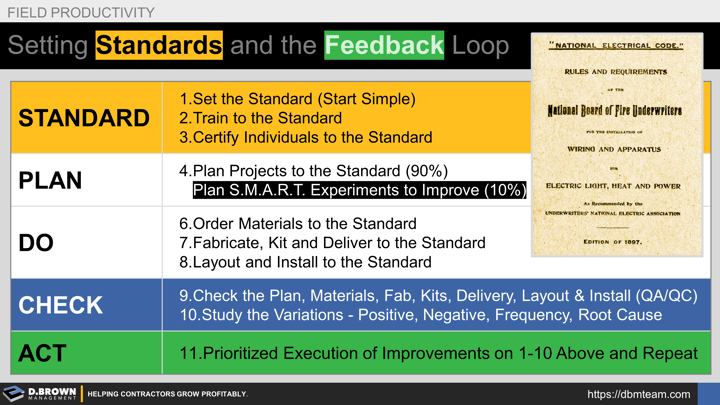

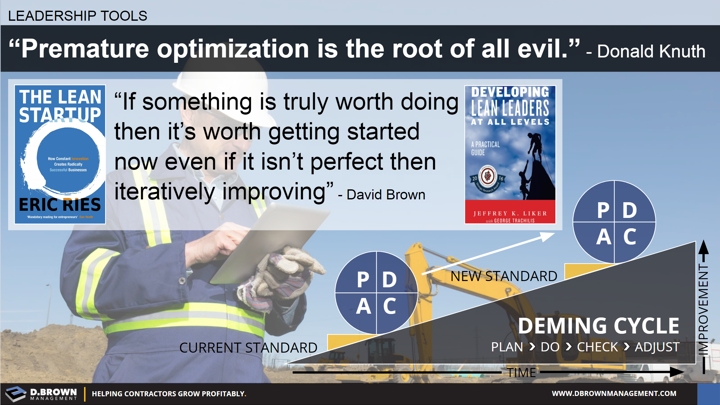

Most people are aware of the term "continuous improvement" and many have heard the acronym PDCA (Plan > Do > Check > Act), also known as the Deming Cycle. Too often, what is missing is a deeper understanding of the standard setting portion of the process.

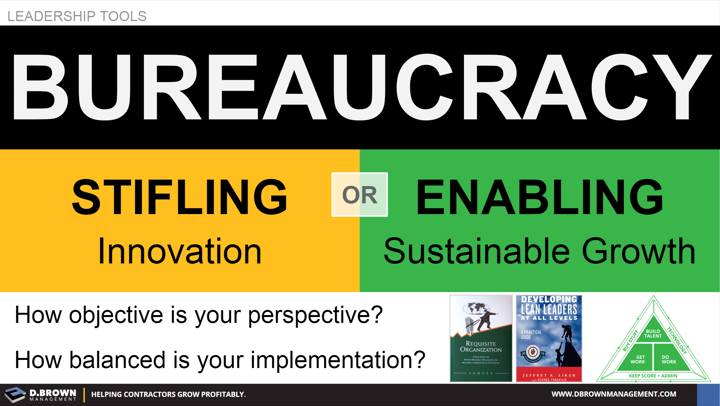

Nearly everyone has worked in or dealt with organizations where there is such a focus on standardized processes that the employees, customers, and suppliers feel stifled by bureaucracy. Because of this, many of us have a negative visceral reaction to anything that seems like too much of a standardized process.

This is what gives bureaucracy a bad name. Also, because this behavior is only exhibited in larger organizations, the negative associations are magnified:

- Standardized Processes = BAD: "We are becoming too big and bureaucratic."

- Growth = BAD: "We will become too big and bureaucratic and then our good talent will leave and our overhead will balloon and our profits will fall."

This is all 100% true. As many construction contractors grow, their people and profits are crushed under the huge weight of stifling bureaucracy. Some to the point of dying.

Also 100% true is that many construction contractors never make it past the first few stages of growth, with failure rates estimated near 30% as studied across various two-year time periods. Over 65% of contractors are under $1M per year in revenues and 95% are under $5M, with only about 0.5% being $20M or more in revenue.

Also 100% true is that some contractors are able to put in just the right level of enabling bureaucracy at each stage of their growth, leading to amazing growth for their customers, people, and profits.

Rather than making the immediate assumption that standardized processes are always bad and bureaucratic and are only associated with big, old, and slow contractors, try to open your perspective and look at it in two ways:

- Bad: Stifling or coercive bureaucracy

- Good: Enabling bureaucracy that allows sustainably profitable growth

Also, recognize that the differences are not static and will change as you grow. The only thing that matters is whether each step in the process is truly adding value to the customer, including pure waste. The process must also be scalable, producing consistent outcomes without overburdening the team, equipment, or other resources.

The alignment of strategy, organizational structure, and standardized process is amazing.

"The purpose of organization is to make ordinary people do extraordinary things."

As you look at the PDCA (Plan > Do > Check > Act) Cycle, notice that the wedge that holds the wheel in place as it climbs the improvement mountain is the standard. Just like driving a piece of equipment up a mountain, the steeper mountains will require more energy to move up and a bigger wheel chock (wedge / standard) to hold the equipment in place. It's also important to balance the process with your stage of growth, working to improve iteratively with each cycle.

1. Set the Standard

Know that your organization already has standards but most of them are implied rather than explicit. Think about terms used, even in the building code standards of our industry, like "Workmanlike Manner" as being an implied standard, whereas NEC (National Electric Code) 358.30 explicitly states "EMT must be secured at least every 10 ft. and within 3 ft. of every outlet box, junction box, device box, cabinet, conduit body, or other termination."

Start simple and iteratively improve over time. Consider that the first edition of the NEC was published in 1897 as a 3X5" handbook of just 58 pages, starting with "General Suggestions" and 1(a) "Generators must be located in a dry place." As of 2020, generators have now been reorganized to No. 445, while the code book has grown to 900 pages plus multiple supplemental books, including NFPA 70E, which is fully dedicated to electrical safety.

These improvements over 123 years and 54 editions have dramatically lowered the incidents of electrical accidents and fires, while massively expanding the integration of electricity into every aspect of our lives. All other building codes and standard specifications have followed similar paths.

As you think about your organization, don't start with the complex. Start with the simplest of statements, documenting your already existing implied standards, i.e. your organization's equivalent of "Generators must be located in a dry place."

Start with the foundational principles for effectiveness within each area of your operation and grow from there. Grab a handful of your foremen and superintendents and write down your "Top 10 Things the Best Crafts People Consistently Do."

As your standards evolve, be clear on which of your standards are "General Suggestions" and which are hard, "Non-Negotiable Standards" that require escalation if they aren't met.

2. Train to the Standard

Writing your standards down is only the beginning. Develop training to ensure that this knowledge is transferred to everyone who needs to know it within your whole organization. This training may include:

- Illustrations, pictures, and videos demonstrating application.

- Delving into the "Why" behind the standard, connecting it to how it adds value to the customer, company, and individual, including how it limits risk.

- Real world examples, both good and bad.

- Hands-on demonstrations.

- Hands-on practice with feedback.

In the building code world, think about the many companies, such as Mike Holt, that produce a myriad of training materials related to building code and the thousands of instructors in apprenticeship programs across the country that train with those materials in combination with the code book itself.

The best companies not only develop their trainers, coaches, and mentors internally but also leverage an extensive network of external resources.

Remember that as the complexity of the task increases, the amount of time it takes and the ratio of coaching to training also increases.

“We don't rise to the level of our expectations, we fall to the level of our training.”

3. Certify to the Standard

As with building codes and craft training, there must be some level of "certification" to ensure that the knowledge has been effectively transferred through the training and the individual knows what to do and how to do it. This is the third level up the pyramid of personal and team productivity. Think about the various state and local tests at the craft level for licensing, along with the regular renewals. Think about the regular requirements to renew your CPR or OSHA 10.

Moving from individual productivity to team productivity requires the ability to teach others built into the culture and capabilities of the organization. This is why the SODOTO (See One >> Do One >> Teach One) method of training and certification is used frequently. Being SHOWN something is not the same as having the ability to DO something.

A few things to consider about your organization in regards to certification:

- Have a separate person certify that someone has demonstrated the skills they were trained for. The person who trained them will often have too many biases (conscious and unconscious) to be effective at certifying the same person they just trained.

- Whenever possible, the certification should occur no sooner than three days after training ends to ensure that the skill was effectively transferred from short-term memory.

- Align elements of your various certifications with your pre-hire screening assessments so that you increase the probability of hiring good team members.

- For key skills or groups of skills, consider clear visual indicators, such as hardhat stickers, that specify various levels. As an example: "Rough-In" may be a skill group that includes installation, quality, safety, and production standards. Levels may be shown progressively as:

- Competent: Can do the job per company standards

- Trainer: Can train others to do the job per the company standards

- Innovator: Has made material improvements to the company standards

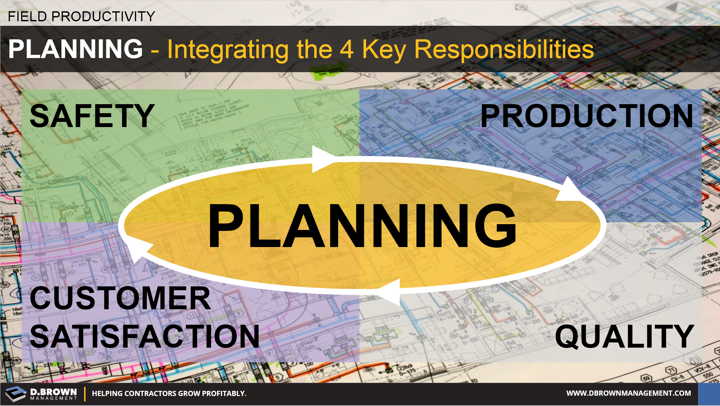

4. Plan Your Projects to the Standard

We are accustomed to planning projects to many standards, including the contract, plans, specifications, building codes, safety regulations, and the myriad of other standards we have to follow, such as working hours, site access, noise, storm water protection, etc.

Start to incorporate your own company standards into every aspect of the project planning process, including estimating, design, layout, materials, fabrication, logistics, scheduling, field installation, and QA/QC.

Identify areas where your standards seem to be in conflict with the other standards on the project, both those that are explicitly defined and those that are merely implied. These are opportunities for improving your own standards and training and for identifying what areas require escalation.

Define clear escalation paths for when your standards can't be met at the planning stage. DO NOT push a problem downstream. Not everything that is planned will work right in the installation, but if it DOESN'T WORK at the planning stage, it most certainly won't work right at the installation stage.

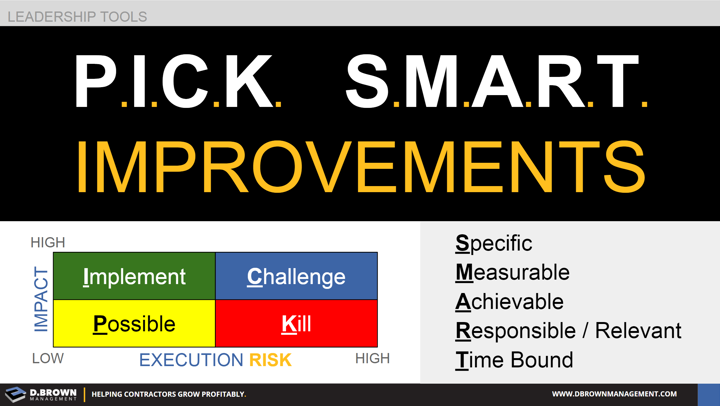

5. Plan S.M.A.R.T. Experiments to Improve on the Standard (10% of the Time)

After reaching a level of consistency with an existing standard and when you see a true opportunity to improve, then build that experiment into the planning process.

- Design your improvement experiments to be S.M.A.R.T. so that you can quantify results against the existing standard, eventually rolling it out as a new standard across the whole company.

- Know that you will likely fail several times before you achieve success. Plan for that and don't "bet the farm" on any single experiment.

- Document your experiments and results, building them into the training so you minimize repeating the same mistakes. Failure is a potent teacher.

6. Order Materials to the Standard and Plan

7. Fabricate, Kit, and Deliver to the Standard and Plan

8. Layout and Install to the Standard

Start with simple and higher-level standards. Always begin with the end in mind: the final installed product should fully meet the expectations of the customer, with each step adding value. As your standards evolve, pay special attention to the interactions between functional areas, both internally and externally, as this is where most mistakes happen and where team cohesion can really start to break down.

Eventually, you will develop clear inputs and outputs for every role and every functional area of your company, which will lead to better hiring, training, and evaluations of your team.

In the future and as your capabilities and reputation grow, you can extend this to the customers, suppliers, and other related parties you choose to work with.

9. Check Planning, Materials, Fabrication, Kits, Delivery, Layout, and Install Against the Standard

Build Quality Assurance (QA) and Quality Control (QC) checks into each part of your value stream.

- Quality Assurance is about prevention by ensuring that the process is being followed and the process itself will lead to consistently good results. Think about routine yet random internal audits to ensure that submittals are being properly managed, including logs, timeliness, filing, and accuracy.

- Quality Control is about detecting outcomes that vary from the standard. Think about a building inspector or the punch lists generated by the architect, engineer, and building owner.

Keep in mind that typically, problems that are allowed to move downstream cost significantly more. Something that is relatively cheap to find and fix at the design stage is likely to cost 10X as much to fix after construction is complete.

There is a balance, Never spend more on QA/QC than you get in return. It is just as important to set standards for the QA/QC process. Experiment to find the right balance. Know that your balance and the areas you focus on will change over time.

Looking back at your standards and your planning, know what level of variation you want to identify with your QA/QC process. Have clarity on when you just identify the variation and when you stop the machine to fix or escalate before moving on.

- Make immediate fixes (countermeasures) where necessary.

- Log all QA/QC variations to study and prioritize longer term improvements.

As with the certification of the training, it is nearly impossible for someone to effectively QA/QC their own work and it is certainly not scalable.

10. Study the Variations - Positive, Negative, Frequency, Quantification, and Root Cause

Study all variations from the standard that are outside of expected limits. Remember that consistency is one critical aspect of lean management.

- Negative variations are obvious opportunities for improvement.

- Positive variations may be indicators of unrecognized improvements or conditions.

- Estimate the frequency of occurrence for what you have logged as part of your QA/QC process and for what you expect to occur over a one-year period of time for your company.

- Estimate the average impact in dollars or hours per occurrence. Where applicable, consider indirect impacts such as increased insurance costs or lost customer opportunities.

- Use Root Cause Analysis (RCA) to categorize them to identify common underlying problems down to the behavioral level.

While the QA/QC process can be done locally where the work happens, it is important to consolidate, track, and manage this from a much higher level in the organization. Whoever ultimately leads this part of the process must have the experience and wisdom to see issues and root causes across all functional areas of the company, along with the leadership ability and authority to implement changes.

Getting to the bottom of an issue will require trust, good questions, and rigorous discussion. Too often, we see companies trying to automate too much of the feedback process, which leads to lots of data but little useful information.

We also see a lot of problems that are diagnosed at the wrong level, and therefore, the "fix" never really works. Examples include:

- Trying to improve change order management processes for project managers when the root cause was within the opportunity selection and contract administration processes.

- Focusing on the quality of the craft labor when the root causes are poor schedule flow and work areas not being ready.

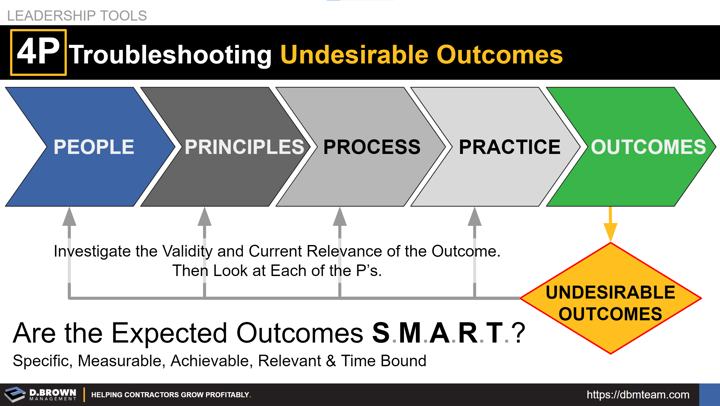

Remember the 4P (People, Principles, Process, Practice) and 4C (Choices, Capabilities, Capacity, Controls) Troubleshooting of Undesirable Outcomes

The last thing to consider is that there are more variables within your control than you think, and the more your process evolves, the more your whole team will see that. Also know that there are variables outside your control, like a freak rainstorm off season that can produce bad outcomes even with a good process. And just as dangerous are good outcomes with a bad process. This is why it is important to study both variations in Quality Assurance (Process) and Quality Control (Outcomes). Only paying attention to outcomes can lead to some very poor decision making, which in poker is known as "Resulting."

11. Prioritized Adjustments to Standards, Planning, Doing, or Checking

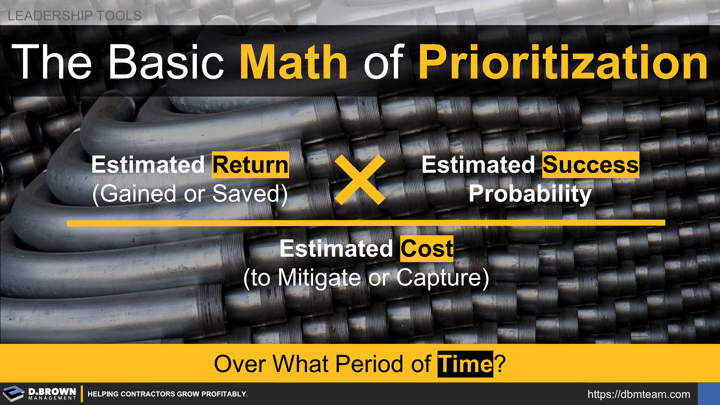

- No organization will ever have all the resources necessary to fix every problem, even if they pencil out to have a good Return on Investment (ROI). You must relentlessly prioritize and execute.

- There is some basic math to prioritization and there are some tools like P.I.C.K. (Possible, Implement, Challenge or Kill) that will help you assess where to best use your resources while helping align your team.

- Identifying problems is the easy part, which is why we spend a lot less time than many consulting firms doing deep assessments to identify all the problems.

- Once you have prioritized the improvements put all your resources into solving them all the way.

- Don't underestimate the value of cleaning up a bunch of nagging little problems. Like change orders, there is a cumulative impact of a bunch of small problems that is often underestimated. (Implement quadrant of the PICK Chart)

- However, don't let the constant focus on small problems distract you from undertaking some of the more challenging projects. (Challenge quadrant of the PICK Chart)

- If you are making changes to your standards, make sure you do it on a regular cadence and align it with training and certification so it can be effectively integrated across the organization.

- Remember that, ultimately, the changes need to be at the cultural level and that starts with leadership. Safety is a perfect example of where compliance efforts and measurements will only get you so far.

This process of continuous improvement will be more difficult and more rewarding that you can imagine. It is not a project, but rather, a way of working that must get built into your daily habits so that it becomes a part of your culture. Remember the basics:

- Set the Standard (Start Simple)

- Train to the Standard

- Certify to the Standard

- Plan your Projects to the Standard (90% of the Time)

- Plan S.M.A.R.T. Experiments Designed to Improve on the Standard (10% of the Time)

- Order Materials to the Standard

- Fabricate, Kit, and Deliver to the Standard

- Layout and Install to the Standard

- Check the Plan, Materials, Fabrication, Kits, Delivery, Layout, and Installation Against the Standard

- Study the Variations - Positive, Negative, Frequency, Quantification, and Root Cause

- Prioritized Execution of Improvements on 1-10 Above and Repeat